Reconsidering Freud's Seduction Theory

Trauma, Denial, and the Betrayal of Survivors in Psychoanalytic History

Abstract

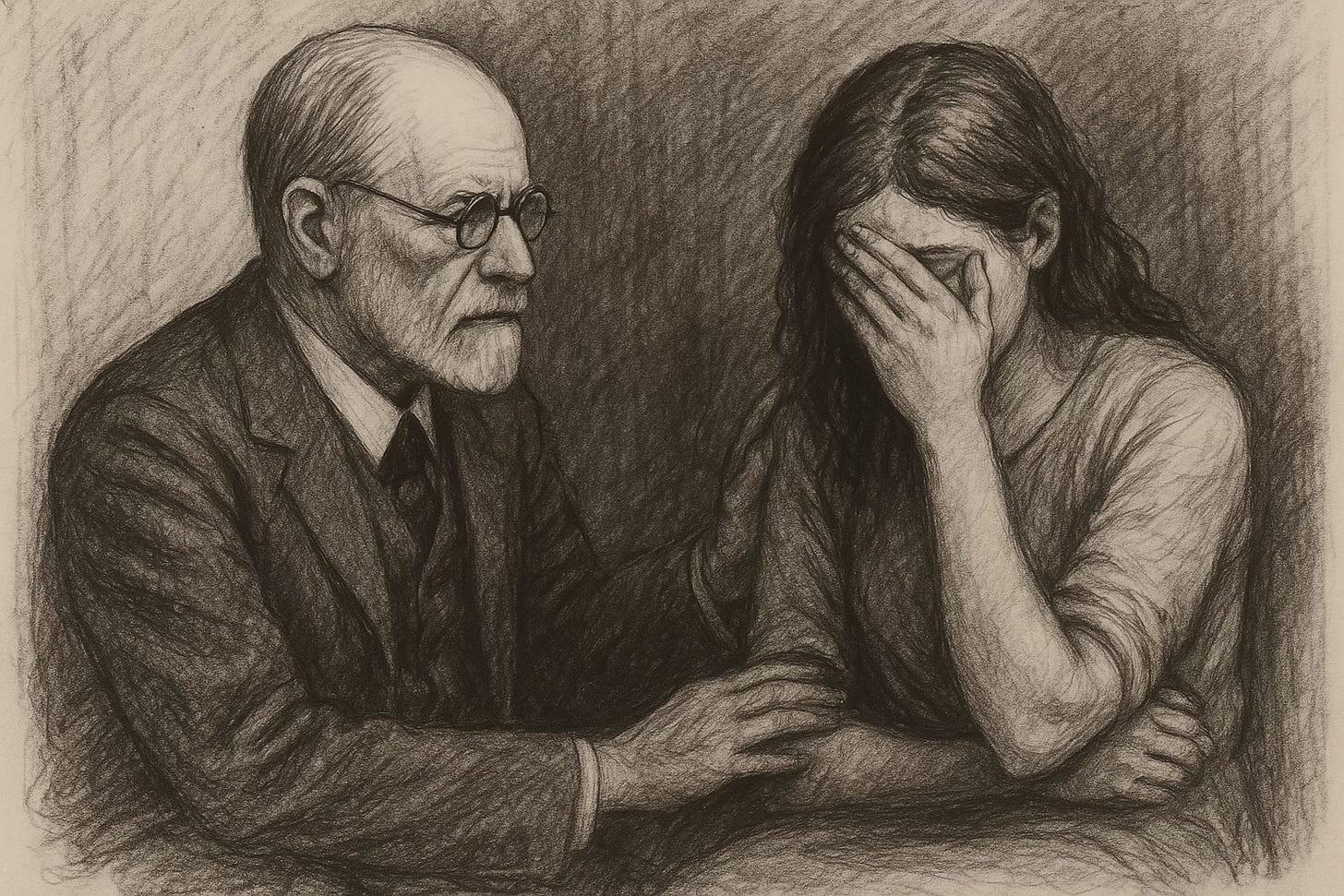

Sigmund Freud’s early seduction theory posited that neuroses stemmed from actual instances of childhood sexual abuse. However, by 1897, under pressure, Freud abandoned this hypothesis in favour of the Oedipus complex, shifting the foundation of psychopathology from real-world trauma to unconscious fantasy. This paper revisits the implications of that theoretical pivot, arguing that had Freud retained the seduction theory, modern psychiatry might have recognized and addressed child sexual abuse much earlier. The Oedipal framework is further critiqued as a culturally specific narrative that may have mystified rather than clarified developmental processes. Revisiting the seduction theory invites a more empirically grounded, survivor-centred approach to psychology, with profound implications for both theory and practice.

Introduction

In the 1890s, Sigmund Freud introduced the seduction theory, asserting that the root of neuroses, particularly hysteria, was early childhood sexual trauma (Masson, 1984). His clinical interviews led him to believe that real abuse, not fantasy, was responsible for the symptoms his patients exhibited. However, by 1897, Freud retracted the theory, suggesting instead that such narratives were manifestations of unconscious wishes and fantasies. This shift inaugurated the dominance of the Oedipus complex in psychoanalysis, which reinterpreted trauma as internal psychodynamic conflict rather than external violation (Freud, 1905/1953). The consequences of this theoretical redirection were far-reaching, shaping a century of psychological discourse that largely dismissed or pathologized survivor testimony.

Freud’s Reversal and the Denial of Trauma

Freud's abandonment of the seduction theory arguably represents a critical moment in the history of psychiatry’s dismissal of trauma. As Masson (1984) contends, Freud’s decision was not simply theoretical but political, reflecting the social impossibility of acknowledging widespread child sexual abuse in the moral climate of late 19th-century Europe. Had Freud maintained his original position, the trajectory of psychology might have centred on external harm, especially interpersonal and systemic violence, as the basis for psychopathology. Instead, the reorientation toward unconscious fantasy opened the door for pathologizing survivor narratives, often branding them as hysterical or delusional (Herman, 1992).

Oedipus and Electra: Overcomplicated or Metaphorical?

The Oedipus and Electra complexes, key components of Freud's later theory, present culturally specific and mythologized narratives about psychosexual development. Critics argue these frameworks are not universally applicable but reflect 19th-century European gender norms and social structures (Chodorow, 1999; Mitchell, 1974). From the perspective of developmental psychology, many of the dynamics Freud mythologized, such as rivalry, identity formation, and attachment, are more effectively explained through contemporary models like attachment theory and family systems theory (Bowlby, 1988; Minuchin, 1974). These approaches contextualize behaviours within relational and environmental systems rather than as symbolic expressions of repressed sexual desire.

Nevertheless, there is psychological value in understanding myths like Oedipus and Electra as metaphors. Jungian and post-Freudian thinkers have interpreted these stories as allegories of individuation, power negotiation, and moral development (Jung, 1968). Yet, this symbolic lens does not excuse the epistemic violence done to real survivors whose experiences were reinterpreted as fantasy. As Herman (1992) argues, myth can illuminate inner life but must not be used to obscure real violations.

The Deeper Implications: Trauma as the Ground of Psyche

Had Freud retained the seduction theory, modern psychology might be fundamentally different. Pathology would be understood not as a disruption of internal drives, but as a response to real-world harms. Trauma would occupy the central explanatory position in psychiatry, likely leading to earlier development of trauma-informed care, survivor advocacy, and systemic accountability (van der Kolk, 2014). Moreover, the cultural silence around child abuse might have been challenged a century earlier, potentially averting generations of institutional complicity.

The substitution of fantasy for violation arguably reflects a broader societal discomfort with acknowledging abuse, particularly abuse embedded within family structures and power hierarchies. The Oedipus complex, in this light, can be interpreted as a culturally coded defence mechanism, displacing blame from adult perpetrators onto the unconscious wishes of children. This theoretical maneuver not only silenced victims but legitimized the very institutions that enabled abuse to continue unchecked.

Conclusion: Revisiting the Seduction Theory as Ethical Imperative

Freud’s abandonment of the seduction hypothesis may represent the original betrayal of trauma survivors in the history of modern psychology. Rather than serving as a pathway to healing, psychoanalysis became a mechanism for reinterpretation, denial, and invalidation. Revisiting the seduction theory is not a call for dogmatic return, but an invitation to reorient psychological theory around real-world harm, embodied experience, and survivor testimony. A psychology rooted in trauma, rather than fantasy, offers not only therapeutic efficacy but moral clarity. In doing so, it transforms the field from one of interpretation to one of justice.

References

Bowlby, J. (1988). A secure base: Parent-child attachment and healthy human development. Basic Books.

This foundational text in attachment theory outlines how early relationships with caregivers shape emotional development and mental health. It contrasts with Freudian psychosexual models by offering a more empirically grounded understanding of childhood needs, making it essential to the critique of the Oedipus complex in the paper.

Chodorow, N. (1999). The reproduction of mothering: Psychoanalysis and the sociology of gender. University of California Press.

Chodorow offers a feminist reinterpretation of Freudian theory, analyzing how gendered roles are socially constructed and reproduced through early family dynamics. Her work is cited to critique the cultural and gender biases embedded in Freud’s Oedipal model.

Freud, S. (1953). Three essays on the theory of sexuality (J. Strachey, Trans.). In J. Strachey (Ed.), The standard edition of the complete psychological works of Sigmund Freud (Vol. 7, pp. 123–246). Hogarth Press. (Original work published 1905)

This is Freud’s seminal work where he formalized the Oedipus complex and replaced the seduction theory with a fantasy-based model of neurosis. It provides the theoretical basis for understanding Freud’s later shift in psychoanalytic focus.

Herman, J. L. (1992). Trauma and recovery: The aftermath of violence, from domestic abuse to political terror. Basic Books.

Herman’s landmark book traces the history of how trauma has been denied and later rediscovered by psychiatry. Her analysis of Freud’s retreat from the seduction theory is critical to understanding how the field marginalized survivor voices for decades.

Jung, C. G. (1968). Man and his symbols. Dell.

Jung explores the psychological significance of myths and symbols, offering a broader, more metaphorical lens through which to view human development. This text is used to argue that myths like Oedipus may reveal cultural truths but should not replace empirical accounts of trauma.

Masson, J. M. (1984). The assault on truth: Freud's suppression of the seduction theory. Farrar, Straus and Giroux.

Masson controversially argues that Freud deliberately suppressed evidence of widespread child sexual abuse to protect psychoanalysis from scandal. His work is central to the argument that Freud’s theoretical reversal had more to do with social pressures than scientific discovery.

Minuchin, S. (1974). Families and family therapy. Harvard University Press.

A foundational text in family systems theory, this book reframes psychological symptoms as products of dysfunctional relational dynamics rather than internal drives. It supports the idea that Freud’s mythic complexes can be better explained through modern systemic approaches.

Mitchell, J. (1974). Psychoanalysis and feminism. Pantheon Books.

Mitchell offers a feminist critique of psychoanalysis, arguing that Freudian theory reflects patriarchal assumptions. Her work is cited to question the universality of the Oedipal narrative and its implications for understanding gender and power.

van der Kolk, B. A. (2014). The Body Keeps the Score: Brain, Mind, and Body in the Healing of Trauma. Viking.

This influential text integrates neuroscience and clinical work to demonstrate how trauma physically reshapes the brain and body. It exemplifies the modern trauma-informed paradigm that might have emerged earlier had Freud retained his seduction theory.