Introduction

Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder (PTSD) is a severe and chronic health condition that arises following exposure to psychologically traumatic events. It is estimated to affect over three hundred million people worldwide, significantly impairing their daily functioning and quality of life. While PTSD is often characterized by symptoms such as intrusive memories, avoidance behaviours, negative alterations in cognition and mood, and hyperarousal, the underlying neurobiological, endocrine, and metabolic mechanisms are complex, making PTSD a whole-body illness. This essay explores the neural structures involved, the biochemical and metabolic changes accompanying the condition, and the long-term implications for affected individuals.

Understanding PTSD: Clinical Overview

Definition and Symptoms

PTSD is defined by the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, Fifth Edition (DSM-5), as the development of characteristic symptoms following personal exposure to actual or threatened death, serious injury/illness, or sexual violence.

The characteristic symptoms of PTSD are divided into four clusters:

1. Intrusive Symptoms: Recurrent, involuntary, and distressing memories or somatic sensations of the traumatic event, nightmares, and flashbacks.

2. Avoidance Symptoms: Efforts to avoid trauma reminders, including thoughts, feelings, people, places, and activities.

3. Negative Alterations in Cognition and Mood: Persistent negative beliefs about oneself or the world, distorted blame of self or others, persistent fear, horror, anger, guilt, or shame, diminished interest in activities, and/or feelings of derealization, depersonalization and detachment or estrangement from others.

4. Hyperarousal Symptoms: include irritability, reckless or self-destructive behaviour, hypervigilance, an exaggerated startle response, problems with concentration, and sleep disturbances.

Epidemiology and Risk Factors

PTSD can affect individuals of any age and background. Risk factors include the severity and proximity of the trauma, previous trauma exposure, pre-existing mental health conditions, lack of social support, and genetic predispositions. While not everyone exposed to trauma will develop PTSD, those who do may experience significant disruptions in their personal, social, and occupational lives.

The Anatomy of PTSD

The neurobiological underpinnings of PTSD involve alterations in various neural structures and body systems.

The Amygdala

Structure and Function

The amygdala, an almond-shaped cluster of nuclei located deep within the temporal lobes, plays a central role in emotional processing, particularly fear and threat detection. It is involved in the encoding and consolidation of emotional memories and the generation of fear responses.

Role in PTSD

In PTSD, the amygdala is often hyperactive, leading to exaggerated fear responses and heightened emotional reactivity. This hyperactivity contributes to the persistence of fear-related memories and the heightened sensitivity to trauma-related cues. The amygdala’s interactions with other brain regions, such as the hippocampus and prefrontal cortex, are also disrupted in PTSD, further exacerbating symptoms.

The Hippocampus

Structure and Function

The hippocampus, located in the medial temporal lobe, is crucial in forming and retrieving declarative memories and regulating stress responses. It plays a key role in contextualizing memories and distinguishing between safe and threatening environments.

Role in PTSD

In individuals with PTSD, the hippocampus often shows reduced volume and impaired function. This atrophy is associated with difficulties in forming coherent narratives of traumatic events and distinguishing between past and present threats. The hippocampus’s impaired function can lead to the generalization of fear responses and difficulties in contextualizing memories, contributing to intrusive memories and hyperarousal persistence.

The Prefrontal Cortex (PFC)

Structure and Function

The prefrontal cortex (PFC), located in the frontal lobes, is involved in higher-order cognitive functions, including decision-making, emotional regulation, and executive control. The PFC includes several subregions, such as the ventromedial prefrontal cortex (vmPFC), which is involved in the processing of risk and fear, playing a role in the extinction of learned fear responses, and the dorsolateral prefrontal cortex (dlPFC), which is involved in domain-general executive control functions such as task switching and task-set reconfiguration, prevention of interference, inhibition, planning, and working memory.

Role in PTSD

In PTSD, the PFC often exhibits reduced activity and connectivity, particularly in the vmPFC and dlPFC. This hypofunction is associated with impaired regulation of emotions and difficulty in suppressing inappropriate fear responses. The PFC’s reduced activity can lead to difficulties in cognitive control, making it harder for individuals to regulate their emotional responses and reduce the impact of trauma-related memories.

The Insula

Structure and Function

The insula, located deep within the lateral sulcus, is involved in interoception (the perception of internal bodily states), emotional processing, and the integration of sensory information. It helps monitor physiological conditions, such as heartbeat and visceral sensations, contributing to self-awareness and the experience of internal sensations and emotions.

Role in PTSD

In PTSD, the insula often shows altered activity, with hyperactivity in the anterior insula and hypoactivity in the posterior insula. This dysfunction can lead to heightened emotional responses, increased interoceptive awareness, and difficulties in emotional regulation. The insula’s role in integrating emotional and sensory information makes it a key player in the heightened emotional reactivity and hyperarousal seen in PTSD.

The Anterior Cingulate Cortex (ACC)

Structure and Function

The anterior cingulate cortex (ACC), located in the frontal lobe, is involved in emotional regulation, decision-making, and cognitive control. It is also involved in processing emotions and regulating autonomic responses to stress.

Role in PTSD

In PTSD, the ACC often shows reduced activity and connectivity. This hypofunction is associated with difficulties in regulating emotions and controlling fear responses. The ACC’s impaired function can lead to persistent emotional dysregulation and difficulties in managing stress, contributing to the chronicity of PTSD symptoms.

The Thalamus

Structure and Function

The thalamus is located in the center of the brain. It acts as a relay station for sensory information, processing and transmitting signals to various cortical areas. The thalamus plays a crucial role in sensory integration and attention.

Role in PTSD

In PTSD, the thalamus can exhibit altered activity, leading to disruptions in sensory processing and attention. These disruptions can contribute to the heightened sensitivity to trauma-related cues and difficulties in filtering out irrelevant stimuli. The thalamus’s role in sensory integration makes it a key player in the sensory and attentional disturbances seen in PTSD.

The Hypothalamus

Structure and Function

The hypothalamus is a small but crucial gland located at the base of the brain. It plays a central role in regulating homeostasis, including body temperature, hunger, thirst, and circadian rhythms. The hypothalamus is also integral in the body’s response to stress through its regulation of the autonomic nervous, and endocrine systems.

Role in PTSD

In PTSD, the hypothalamus is involved in the dysregulation of the hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal (HPA) axis, which is a central stress response system. The hypothalamus releases corticotropin-releasing hormone (CRH) in response to stress, which signals the pituitary gland to release adrenocorticotropic hormone (ACTH). Dysregulation in this process can lead to abnormal cortisol levels, either elevated or blunted, contributing to the chronic stress response seen in PTSD patients.

Pituitary Gland

Structure and Function

The pituitary gland is located below the hypothalamus. It is divided into the anterior and posterior pituitary and is responsible for releasing various hormones that regulate critical body functions, including growth, metabolism, and reproduction.

Role in PTSD

The anterior pituitary releases ACTH in response to CRH from the hypothalamus. ACTH then stimulates the adrenal glands to produce cortisol. In PTSD, the pituitary gland may show altered responsiveness to CRH, leading to dysregulated ACTH release and subsequent cortisol imbalances. This dysregulation can affect the body’s ability to appropriately respond to and recover from stress.

Adrenal Glands

Structure and Function

The adrenal glands are small, triangular glands located on top of each kidney. They consist of the adrenal cortex and adrenal medulla, which produce different hormones. The adrenal cortex produces corticosteroids, including cortisol, while the adrenal medulla produces catecholamines, such as adrenaline (epinephrine) and noradrenaline (norepinephrine).

Role in PTSD

In PTSD, the adrenal glands are often overactive, leading to elevated levels of cortisol and catecholamines. This hyperactivity can result in symptoms such as hyperarousal, anxiety, and an exaggerated startle response. Chronic exposure to high cortisol levels can also impair cognitive function and memory, contributing to the persistence of traumatic memories and difficulty in emotional regulation.

Thyroid Gland

Structure and Function

The thyroid gland, located in the neck, produces hormones that regulate metabolism, energy levels, and growth. Thyroid hormones, such as thyroxine (T4) and triiodothyronine (T3), are essential for maintaining metabolic homeostasis.

Role in PTSD

Thyroid function can be affected in PTSD, with some individuals exhibiting altered levels of thyroid hormones. Hyperthyroidism (excess thyroid hormone) can exacerbate anxiety and hyperarousal symptoms, while hypothyroidism (reduced thyroid hormone) can contribute to depression and fatigue. Monitoring and managing thyroid function can be important in the comprehensive treatment of PTSD.

Gonadal Glands (Ovaries and Testes)

Structure and Function

The gonadal glands, including the ovaries in females and testes in males, produce sex hormones such as estrogen, progesterone, and testosterone. These hormones regulate reproductive functions and secondary sexual characteristics.

Role in PTSD

Sex hormones can influence the severity and expression of PTSD symptoms. For instance, fluctuations in estrogen levels during the menstrual cycle can affect mood and stress reactivity in women with PTSD. Additionally, low testosterone levels in men have been associated with increased vulnerability to stress and depression. Hormonal therapies that balance sex hormone levels may help alleviate some PTSD symptoms.

Pancreas

Structure and Function

The pancreas is a large gland behind the stomach that produces insulin and glucagon, hormones regulating blood sugar levels.

Role in PTSD

Stress and cortisol dysregulation in PTSD can affect glucose metabolism, leading to insulin resistance and metabolic disturbances. Managing blood sugar levels through diet, exercise, and medication can be important for overall health in individuals with PTSD.

The Autonomic Nervous System (ANS)

Structure and Function

The autonomic nervous system is a component of the peripheral nervous system (sensory and motor nerves that branch out from the brain and spinal cord) that signal involuntary physiologic processes, including heart rate, blood pressure, respiration, digestion, and sexual and survival arousal. The ANS contains three anatomically distinct divisions: sympathetic, parasympathetic, and enteric.

Role in PTSD

PTSD is characterized by tonic autonomic hyperarousal.

Sympathetic Nervous System (SNS)

Structure and Function

The sympathetic nervous system (SNS) is made up of sensory and motor nerves that arise from near the middle of the spinal cord, beginning at the first thoracic vertebra and thought to extend to the second or third lumbar vertebra. These nerves provide sensory input and motor output to the central nervous system (CNS), which is responsible for reflexive action and the body’s fight-or-flight response.

Role in PTSD

The SNS governs the body’s “flight or fight” response and controls the mobilization of physiological resources to prepare for physical activity in response to environmental challenges. In PTSD, there is chronic hyperactivation of the SNS, keeping the body aroused and prepared for danger even when there is none.

Parasympathetic Nervous System (PNS)

Structure and Function

The parasympathetic nervous system (SNS) is composed of sensory and motor nerves exiting from the brain stem and the spinal cord's sacral region. These nerves counterbalance the SNS to promote rest, recovery, and digestion.

Role in PTSD

In PTSD, the PNS often shows reduced activity, persistent hypoarousal and difficulty in achieving homeostasis due to imbalanced autonomic regulation, resulting in impaired relaxation and the chronic stress response characteristic of PTSD.

Enteric Nervous System (ENS)

Structure and Function

The enteric nervous system (ENS) is located within the walls of the GI tract, extending from the esophagus to the anal canal. The ENS regulates the major enteric processes such as immune response, detecting nutrients, motility, microvascular circulation, intestinal barrier function, and epithelial secretion of fluids, ions, and bioactive peptides.

Possible Role in PTSD

The ENS interacts with the central nervous system (CNS) through the gut-brain axis. This bidirectional communication is crucial in understanding the role of the ENS in PTSD.

Vagus Nerve: The vagus nerve is a major conduit for communication between the gut and the brain. It transmits signals from the ENS to the CNS, influencing mood, stress responses, and emotional regulation. Dysregulation of this pathway can exacerbate PTSD symptoms.

Neurotransmitters: The ENS produces neurotransmitters like serotonin, which plays a crucial role in mood regulation. Approximately 90% of the body’s serotonin is produced in the gut. Alterations in gut-derived serotonin can impact CNS serotonin levels, affecting mood and anxiety in PTSD.

Gut Microbiota: The composition of gut microbiota can influence ENS function and, in turn, affect brain function and behavior. Dysbiosis has been linked to various psychiatric conditions, including PTSD.

Microbial Metabolites: Gut bacteria produce metabolites like short-chain fatty acids (SCFAs) that can modulate brain function. Alterations in these metabolites can impact inflammation, neurotransmission, and stress responses.

Biochemistry, Structural Changes and Neural Connectivity of PTSD

Biochemistry

Core neurochemical features of PTSD include abnormal regulation of catecholamines (dopamine, norepinephrine, and epinephrine), serotonin, amino acids, peptides, and opioid neurotransmitters (enkephalins, endorphins, dynorphins, and nociceptin), each of which is found in brain circuits that regulate/integrate stress and fear responses. The biochemistry of PTSD is very complex and would take up more space than I have available, so I have limited this section to some key neurotransmitters/hormones.

Glutamate: Increased levels of glutamate, the primary excitatory neurotransmitter, have been observed in PTSD, leading to heightened neuronal excitability and stress responses.

Gamma-Aminobutyric Acid (GABA): Reduced GABAergic activity, which normally inhibits excessive neuronal firing, is associated with anxiety and hyperarousal in PTSD.

Serotonin: Dysregulation of the serotonin system is linked to mood disturbances, anxiety, and aggression in PTSD.

Norepinephrine: Elevated norepinephrine levels contribute to hyperarousal, increased heart rate, and heightened stress responses in PTSD. Medications like prazosin, which block norepinephrine receptors, can help mitigate these symptoms.

Dopamine: Alterations in dopamine signalling are associated with reward processing and motivation issues in PTSD, potentially contributing to anhedonia and emotional numbing.

Structural and Functional Changes

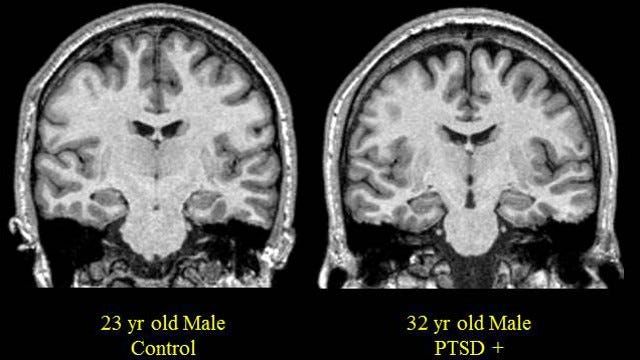

Neuroimaging studies have revealed significant structural and functional brain changes in individuals with PTSD. These include changes in the volume of several areas of the brain, including the amygdala, anterior cingulate cortex, hippocampus, parahippocampal gyrus, prefrontal cortex, temporal cortex, and insula

Increased Amygdala Activity: Overactivation and hyperactivity in the amygdala are linked to exaggerated fear responses and emotional dysregulation.

Reduced Hippocampal Volume: Chronic stress and elevated cortisol levels are thought to contribute to hippocampal atrophy, which impairs memory formation and contextualization.

Decreased PFC Activity: Reduced activity in the PFC impairs executive functions and the ability to regulate emotions and stress responses.

Neural Connectivity

PTSD is associated with changes in the connectivity between key brain structures. Circuits or networks are connections of neurons joining key neural structures.

Amygdala-Prefrontal Cortex Connectivity

This circuit is crucial for regulating fear responses. In PTSD, impaired connectivity between the amygdala and PFC results in diminished top-down control over fear responses, leading to heightened emotional reactivity and difficulties in emotional regulation.

Amygdala-Hippocampus Connectivity

Connectivity between the hippocampus and amygdala is essential for contextualizing fear memories. Disruption in this circuit can lead to the overgeneralization of fear and persistent intrusive memories.

Hippocampus-Prefrontal Cortex Connectivity

Connectivity between the hippocampus and prefrontal cortex is essential for contextual understanding of fear, extinction and inhibition of fear conditioning. Disruption may lead to overgeneralization of fear signals and delayed extinction of fear response.

Salience, Default Mode and Central Executive Networks

Salience Network (SN) Comprising the insula and anterior cingulate cortex (ACC), this network detects and prioritizes salient stimuli. Dysregulation in the salience network can lead to an exaggerated perception of threat and hypervigilance in PTSD.

The Default Mode Network (DMN) The DMN is composed primarily of the cortical regions located across the brain’s mid-line, including the posterior cingulate cortex, the precuneus, and the medial prefrontal cortex. It is a neurological structure activated when the brain is at ‘rest’. The DMN is known to be atypically active during PTSD when an individual engages in introspective activities such as daydreaming, contemplating the past or the future, or thinking about the perspective of someone else. Research shows that childhood maltreatment negatively impacts the development of the DMN, which begins maturation during childhood and does not end until early adulthood. If the trauma(s) is repeated, the DMN will be biased towards the trauma and can re-experience or relive it as long as the trauma remains unprocessed.

Central Executive Network (CEN) connects areas of the dorsolateral prefrontal cortex and posterior partial cortices to support higher-order cognitive processes, including regulating emotions, behaviour, and attention control. CEN connectivity is believed to moderate trauma symptom severity, while decreased connectivity is believed to increase symptom severity.

SN, DMN, CEN Internetwork Connectivity

Research suggests PTSD may be characterized by a weakly connected and hypoactive default mode network (DMN) and central executive network (CEN), that are putatively destabilized by an overactive and hyperconnected salience network (SN).

Learning, Memory and Long-Term Implications of PTSD

Fear Conditioning and Extinction

One of the core mechanisms underlying PTSD is abnormal fear conditioning and extinction. Fear conditioning occurs when a neutral stimulus becomes associated with a traumatic event, leading to a fear response when the stimulus is encountered again. Extinction is the process by which this conditioned response diminishes over time when the stimulus is repeatedly presented without the traumatic event.

In PTSD, individuals exhibit impaired extinction learning, meaning the conditioned fear response persists even in the absence of danger. This impairment is linked to dysfunctions in the amygdala, hippocampus, and PFC, which disrupt the normal processing and regulation of fear.

Memory Consolidation and Retrieval

Memory consolidation is the process by which short-term memories are stabilized into long-term memories. PTSD is characterized by alterations in this process, particularly in how traumatic memories are consolidated and retrieved. The hippocampus, which is vital for contextualizing memories, is often damaged or underactive in PTSD, leading to fragmented and intrusive recollections of the trauma.

The overactive amygdala further exacerbates these memory issues by enhancing the emotional intensity of the memories. This combination of hyperactive emotional responses and impaired contextualization creates persistent and distressing traumatic memories that are difficult to suppress or manage.

Long Term Implications

The brain injuries and neurobiological changes associated with PTSD have significant long-term implications for affected individuals. These implications can impact cognitive, emotional, and social functioning, as well as overall physical health.

Cognitive Impairments

PTSD-related brain changes can lead to various cognitive impairments, including:

Memory Problems: Impaired hippocampal function can result in difficulties with memory consolidation and retrieval, leading to fragmented and intrusive memories.

Attention and Concentration: Altered PFC activity can cause problems with attention, concentration, and executive functioning, affecting daily tasks and occupational performance.

Learning Difficulties: Impaired fear extinction and abnormal memory processing can hinder the ability to learn new information and adapt to new situations.

Emotional and Behavioral Dysregulation

The emotional and behavioral consequences of PTSD-related brain injuries are profound and can include:

Emotional Instability: Hyperactivity in the amygdala and reduced PFC regulation can lead to heightened emotional responses, mood swings, and difficulty managing emotions.

Hyperarousal and Hypervigilance: Dysregulation of the HPA axis and elevated norepinephrine levels contribute to persistent hyperarousal and hypervigilance, leading to chronic stress and anxiety.

Avoidance Behaviors: To cope with distressing memories and emotions, individuals with PTSD may engage in avoidance behaviors, which can limit their social interactions and activities.

Social and Interpersonal Challenges

PTSD can significantly impact social and interpersonal functioning:

Relationship Strain: Emotional instability, irritability, and avoidance behaviors can strain relationships with family, friends, and colleagues, leading to social isolation.

Trust Issues: Traumatic experiences and hypervigilance can lead to difficulties in trusting others, further complicating social interactions and support systems.

Occupational Impacts: Cognitive impairments, emotional dysregulation, and social difficulties can affect job performance and career advancement, potentially leading to economic instability.

Physical Health Consequences

The neurobiological changes in PTSD can also have broader physical health implications:

Chronic Stress: Dysregulation of the HPA axis and persistent hyperarousal can lead to chronic stress, which is associated with various physical health problems, including cardiovascular disease, hypertension, and immune system dysfunction.

Sleep Disturbances: PTSD often involves sleep disturbances, such as insomnia and nightmares, which can contribute to overall health deterioration and exacerbate other symptoms.

Comorbid Psychiatric Conditions: PTSD is frequently comorbid with other mental health conditions, such as depression and anxiety disorders, as well as substance use disorders, which can further complicate treatment and recovery.

Metabolic and Inflammation-Related Disease: PTSD is known to have a long-term connection to increased incidence of diseases related to metabolic dysfunction and inflammation, such as obesity, insulin resistance, diabetes, and cardiovascular and pulmonary disease.

Inflammation and Metabolic Consequences

The metabolic aspects of PTSD involve changes in the body’s biochemical processes, affecting both brain function and overall physical health. While complex, many long-term health complications are believed to be the result of changes in endocrine regulation, receptor sensitivity, inflammatory response, oxidative stress, metabolic syndrome, and brain energy metabolism.

Hypothalamus-Pituitary-Adrenal (HPA) Axis Dysregulation

Cortisol Levels: PTSD often involves altered cortisol levels, which can be either elevated or blunted. Cortisol is a key stress hormone, and its dysregulation can lead to chronic stress and inflammation.

Glucocorticoid Receptor Sensitivity: Changes in glucocorticoid receptor sensitivity can affect how the body responds to stress, influencing the feedback loop of the HPA axis.

Inflammatory Response

Pro-inflammatory Cytokines: PTSD is associated with elevated levels of pro-inflammatory cytokines (e.g., IL-6, TNF-α). Chronic inflammation can contribute to both physical and mental health problems.

Immune System Alterations: Dysregulated immune function can lead to increased susceptibility to infections and autoimmune diseases.

Oxidative Stress

Reactive Oxygen Species (ROS): Increased oxidative stress in PTSD can damage cells and tissues, contributing to neurodegeneration and other health issues.

Antioxidant Defense: Impaired antioxidant defenses can exacerbate oxidative damage, affecting brain function and overall health.

Metabolic Syndrome

Insulin Resistance: PTSD is associated with an increased risk of insulin resistance, which can lead to type 2 diabetes and other metabolic disorders.

Obesity: Higher rates of obesity and related metabolic conditions are observed in individuals with PTSD, possibly due to stress-related eating behaviours and metabolic alterations.

Brain Energy Metabolism

Glucose Metabolism: Changes in glucose metabolism in the brain can affect cognitive function and emotional regulation. Hypometabolism in certain brain regions, like the prefrontal cortex, is often observed.

Mitochondrial Function: Impaired mitochondrial function can lead to reduced energy production, contributing to fatigue and cognitive impairments.

Treatment and Management of PTSD.

Pharmacotherapy

Pharmacotherapy involves the use of medications to alleviate the mood-altering and sleep symptoms of PTSD. While medications are not a cure for PTSD and do not address the underlying trauma, they can play a significant role in managing some of the more distressing symptoms, while other therapeutic modalities work to address the core trauma. Pharmacotherapy is purely augmentative and should not be viewed or used as a primary or sole treatment for PTSD.

Selective Serotonin Reuptake Inhibitors (SSRIs)

SSRIs, such as sertraline and paroxetine, are commonly prescribed for PTSD. They work by increasing the levels of serotonin, a neurotransmitter that influences mood, in the brain. SSRIs have been shown to reduce symptoms of depression and anxiety in PTSD patients, improving overall functioning. They are often considered a first-line treatment for PTSD.

Serotonin-Norepinephrine Reuptake Inhibitors (SNRIs)

SNRIs, such as venlafaxine, increase the levels of both serotonin and norepinephrine in the brain. These medications can be effective in treating the mood and anxiety symptoms associated with PTSD. SNRIs are sometimes used when SSRIs are not effective or cause intolerable side effects.

Prazosin

Prazosin, an alpha-1 adrenergic receptor antagonist, is commonly used to treat nightmares and sleep disturbances in PTSD patients. By blocking the effects of norepinephrine, prazosin can help reduce the frequency and intensity of trauma-related nightmares, leading to better sleep quality.

Other Medications

Other medications, such as benzodiazepines, antipsychotics, and mood stabilizers, may be prescribed in certain cases. However, these are generally used with caution due to potential side effects and the risk of dependence, particularly with benzodiazepines.

Psychotherapy

Peer Group Therapy: Group therapy provides a supportive environment where individuals with PTSD can share their experiences, learn from others, and develop coping strategies. This is especially useful when issues of scalability are an issue or when waitlists delay access to therapists.

Eye Movement Desensitization and Reprocessing (EMDR): EMDR is an integrative psychotherapy approach where the therapist guides the patient to recall traumatic memories while simultaneously engaging in bilateral stimulation, such as eye movements or tapping. This process is believed to facilitate the reprocessing of traumatic memories, reducing their emotional intensity and helping patients develop healthier coping mechanisms.

Mindfulness-Based Therapies: Mindfulness practices, such as mindfulness-based stress reduction (MBSR) and mindfulness-based cognitive therapy (MBCT), can help individuals with PTSD develop greater awareness of their thoughts, emotions, and body sensations and practice of downregulating ANS stimulation to reduce stress and improve emotional regulation.

Polyvagal Theory: Polyvagal theory emphasizes safety and sociality as a core human process that helps to mitigate threats and downregulate ANS overstimulation to support positive psychological and physical health. More specifically, it highlights the importance that the parasympathetic nervous system and vagal circuits play in the neurophysiological mechanisms related to trauma and trauma responses.

Music Therapy: Music therapy works along the same lines as polyvagal theory. Music and the social company of others are used to downregulate the ANS and allow the individual to experience and express emotions in a safe social environment. Passive music therapy is the act of listening to music to relax, improve mood, or allow the listener to focus on something else besides a difficult or triggering memory. Active music therapy is the act of creating music to relax or process negative emotions or memories.

Sensorimotor Psychotherapy: The sensorimotor psychotherapy method focuses on addressing the physiological as well as psychological effects of traumatic experiences by supporting clients to explore how past traumatic experiences affect them somatically.

Hypnosis: Hypnotherapy provides controlled access to memories otherwise kept out of consciousness. New uses of hypnosis in the psychotherapy of PTSD victims involve coupling access to the dissociated traumatic memories with positive restructuring of those memories.

Internal Family Systems (IFS): IFS therapy focuses on enhancing the ability to attend to difficult and distressing internal experiences (i.e. “vulnerable parts”) mindfully and with self-compassion (i.e. from the Self), to increase the capacity to successfully “be with” or tolerate and process traumatic material.

Trauma-Focused Cognitive Behavioral Therapy (TF-CBT): TF-CBT is specifically designed for children and adolescents with PTSD. It combines trauma-sensitive interventions with cognitive behavioural techniques. TF-CBT involves the child and often their caregivers in the treatment process, helping the child develop coping skills, process traumatic memories, and improve overall functioning.

Narrative Exposure Therapy (NET): NET involves creating a detailed narrative of the traumatic experiences, helping patients integrate their memories into a coherent story and reducing the emotional impact of the trauma.

Prolonged Exposure Therapy (PE): PE involves gradually exposing the patient to trauma-related memories, feelings, and situations in a controlled and safe environment. This exposure helps reduce the power of the traumatic memories and desensitizes the patient to trauma-related triggers.

Cognitive Processing Therapy (CPT): CPT focuses on identifying and challenging distorted beliefs related to the trauma. Patients learn to reframe negative thoughts and develop a more balanced perspective on the trauma and its impact.

Complementary Therapies

Yoga, Tai Chi, and Meditation: Practices such as yoga, Tai Chi and meditation can help individuals with PTSD reconnect with their bodies, develop relaxation skills, reduce stress, and improve emotional regulation.

Comprehensive Care Strategies

Effective management of PTSD often involves a combination of treatments and a holistic approach that addresses the various aspects of the disorder.

Integrated Treatment Plans

An integrated treatment plan combines pharmacotherapy and psychotherapy tailored to the individual’s needs. This approach ensures that both the biological and psychological aspects of PTSD are addressed, leading to better outcomes.

Multidisciplinary Care

A multidisciplinary approach involves a team of healthcare providers, including psychiatrists, psychologists, social workers, and primary care physicians. This team works together to provide comprehensive care, addressing the patient's medical, psychological, and social needs.

Support Systems and Social Support

Social support is crucial for individuals with PTSD. Support from family, friends, and support groups can provide emotional comfort, reduce isolation, and enhance treatment outcomes. Educating caregivers and loved ones about PTSD can help them provide better support and understanding.

Self-Help and Coping Strategies

Encouraging individuals with PTSD to engage in self-help and coping strategies can empower them to take an active role in their recovery. These strategies may include:

Regular Exercise: Physical activity can reduce stress, improve mood, and enhance overall well-being.

Healthy Lifestyle Choices: Maintaining a balanced diet, getting adequate sleep, and avoiding alcohol and drugs can support recovery.

Stress Management Techniques: Techniques such as deep breathing, progressive muscle relaxation, and mindfulness can help manage stress and anxiety.

Prevention and the Future of PTSD Treatment

Research into PTSD treatment is ongoing, and several emerging therapies show promise in improving outcomes for individuals with PTSD.

Pharmacological Advances

Ketamine: Ketamine, an anesthetic with rapid-acting antidepressant properties, has shown potential in reducing PTSD symptoms. It is believed to work by modulating glutamate activity in the brain. While ketamine is not yet widely used for PTSD, clinical trials are ongoing.

MDMA-Assisted Therapy: MDMA (3,4-methylenedioxymethamphetamine) is being studied as an adjunct to psychotherapy for PTSD. Preliminary research suggests that MDMA can enhance the therapeutic process by reducing fear and increasing emotional openness, making it easier for patients to engage with traumatic memories in therapy.

Psychelytic and Psychedelic Enhanced Therapies: These are therapies that use psychoactive substances like LSD, Psilocybin, DMT, or Mescaline in varying doses to alter consciousness to facilitate communication and introspection or in higher doses for more profound psychological change.

Neuromodulation Techniques

Transcranial Magnetic Stimulation (TMS): TMS is a non-invasive procedure that uses magnetic fields to stimulate nerve cells in the brain. It has shown promise in reducing PTSD symptoms, particularly in patients who do not respond to traditional treatments.

Electroconvulsive Therapy (ECT): ECT is sometimes used in severe cases of PTSD, particularly when comorbid with major depression. While it is an invasive procedure, it can be effective in reducing symptoms and improving mood.

Virtual Reality Exposure Therapy (VRET): VRET uses virtual reality technology to create immersive simulations of trauma-related environments. This controlled exposure can help patients confront and process traumatic memories in a safe and controlled setting. VRET has been particularly useful for treating combat-related PTSD in veterans.

Prevention and Early Intervention

Preventing PTSD or mitigating its severity through early intervention is an important aspect of managing the disorder.

Psychologically Safe Environments: By identifying and addressing issues like bullying, discrimination, and other forms of structural violence, we can create psychologically safe school, work, and life environments. The danger imposed by wars, economic class conflict, and oppressive practices does not need to exist.

Crisis Intervention & Debriefing: Providing immediate psychological support and safety following a traumatic event may help prevent the development of PTSD. This can include psychological first aid and early counselling. This also includes providing psychological support following profound medical events like life-threatening accidents, illnesses, and surgeries.

Resilience Training: Teaching individuals in high-risk jobs or environmental circumstances resilience skills, such as stress management, personal de-escalation, and positive coping strategies, can enhance their ability to cope with trauma and reduce the risk of developing PTSD.

Screening and Monitoring: Regular screening for PTSD symptoms in high-risk populations, such as military personnel, first responders, and survivors of natural disasters, can facilitate early identification and intervention.

Conclusion

The treatment and management of PTSD require a multifaceted approach that addresses the complex interplay of biological, psychological, and social factors. Comprehensive care strategies that integrate multidisciplinary care, support systems, safety-focused policy, and self-help strategies are essential for promoting recovery and improving the quality of life for individuals with PTSD. By continuing to advance our understanding of PTSD and developing innovative treatment approaches, we can provide better support and hope for those affected by this challenging health condition.